Eugenio Montale

Sometimes

regarded as the greatest Italian poet since Leopardi (1798-1837),

Eugenio Montale was born in Genoa in 1896, was awarded the Nobel Prize

in literature in 1975, and died in Milan in 1981. He served in the

infantry in World War I, and settled in Milan in 1948, where he became

the chief literary critic for Italy's foremost newspaper, the Corriere

della Sera. He was also a music critic and a translator, and, for

his courageous opposition to fascism, was made a lifetime member of

the Italian Senate in 1967. Montale's

poetry is deeply personal, at times almost hermetic. Often it is addressed

to an unknown "you" who, not infrequently, is dead, or to

certain women, presented under fictive names (in the manner of classical

and Renaissance poets), who played important roles in his real and

imaginative lives. They are called Esterina, Gerti, Liuba, Vixen,

Dora Markus, Mosca, and Clizia. Liuba, for example, was someone he

glimpsed for only a few minutes in a railway station, where she was

fleeing from Italy's Fascist, anti-Jewish laws. Dora Markus was someone

he never met; she was, he explained, "constructed from a photograph

of a pair of legs" sent him by a friend. Nevertheless, as one

of his finest translators, William Arrowsmith, declares, "the

poem devoted to her is no mere exercise in virtuoso evocation; it

is the objectification of the poet's affinity for a personal truth,

the existential meaning of a given fragment. 'The poet's task,' Montale

observed, 'is the quest for a particular, not general, truth.'"

His poems almost always deal with fragmentary experience, the meaning

of which is either obscure or, possibly, terrifyingly absent. As a

poet, he had a preoccupation with images of limitation. This is manifested,

Arrowsmith writes, in the form of "walls, barriers, frontiers,

prisons, any confining enclosure that makes escape into a larger self

or a new community impossible. Hence too his intractable refusal to

surrender to any ideology or sodality, whether Communist or Catholic."

Sometimes

regarded as the greatest Italian poet since Leopardi (1798-1837),

Eugenio Montale was born in Genoa in 1896, was awarded the Nobel Prize

in literature in 1975, and died in Milan in 1981. He served in the

infantry in World War I, and settled in Milan in 1948, where he became

the chief literary critic for Italy's foremost newspaper, the Corriere

della Sera. He was also a music critic and a translator, and, for

his courageous opposition to fascism, was made a lifetime member of

the Italian Senate in 1967. Montale's

poetry is deeply personal, at times almost hermetic. Often it is addressed

to an unknown "you" who, not infrequently, is dead, or to

certain women, presented under fictive names (in the manner of classical

and Renaissance poets), who played important roles in his real and

imaginative lives. They are called Esterina, Gerti, Liuba, Vixen,

Dora Markus, Mosca, and Clizia. Liuba, for example, was someone he

glimpsed for only a few minutes in a railway station, where she was

fleeing from Italy's Fascist, anti-Jewish laws. Dora Markus was someone

he never met; she was, he explained, "constructed from a photograph

of a pair of legs" sent him by a friend. Nevertheless, as one

of his finest translators, William Arrowsmith, declares, "the

poem devoted to her is no mere exercise in virtuoso evocation; it

is the objectification of the poet's affinity for a personal truth,

the existential meaning of a given fragment. 'The poet's task,' Montale

observed, 'is the quest for a particular, not general, truth.'"

His poems almost always deal with fragmentary experience, the meaning

of which is either obscure or, possibly, terrifyingly absent. As a

poet, he had a preoccupation with images of limitation. This is manifested,

Arrowsmith writes, in the form of "walls, barriers, frontiers,

prisons, any confining enclosure that makes escape into a larger self

or a new community impossible. Hence too his intractable refusal to

surrender to any ideology or sodality, whether Communist or Catholic."

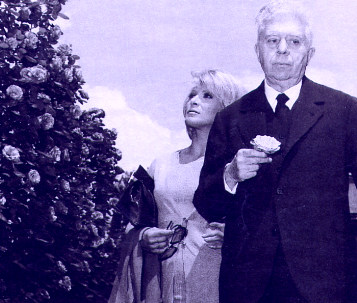

In 1927 Montale fell in love with a married woman, who left her husband

in 1939 and moved in with him. He called her, half-affectionately,

half-mockingly, Mosca (or Fly), a name he might have borrowed from

Ben Jonson's Volpone. She was a plain woman with poor eyesight, but

he remained devoted to her, and when her husband died in 1958, they

entered into a marriage that lasted until her death five years later.

Another woman who would figure prominently in Montale's work was an

American scholar he met in 1932 named Irma Brandeis--later to become

the author of a brilliant study of Dante's Divine Comedy called The

Ladder of Vision, an examination of segments of Dante's great epic

without recourse to any credence in its theology. In Montale's poems

she becomes his Beatrice, a woman of more-than-human gentleness and

perfection. (In an interview, Montale said the women in his poems

were "Dantesque, Dantesque," by which he meant, suggests

the poet/scholar Rosanna Warren, they were spiritualized, not fully

individualized beings.) He gave this American, a figure of majestic

spiritual importance to him, the name of Clizia (might this be derived

from ecclesia?). Arrowsmith calls her "the absent center of the

poet's life. . . . Cliziàs sacrifice of physical love"

allows her to become "her lover's spiritual salvation,"

and redeems "all those who, like Montale, were suffering the

darkness of the Fascist years and human evil generally. She 'redeems

the time,'" in a phrase borrowed from T. S. Eliot.

Montale was a learned autodidact and a highly allusive poet, a matter

that adds to the difficulties and puzzles of his poems. His literary

influences, for example, include Plato, the Bible, Dante and the dolcestilnovisti

of his circle, Petrarch, Shakespeare and the English Metaphysical

poets, Browning, Henry James, Hopkins, Baudelaire, Mallarmé,

Jammes, and Valéry, as well as Eliot.

A word needs to be said about William Arrowsmith, Montale's chief,

and among his best, translators. He was a classicist who has translated

Euripides, Aristophanes, and Petronius, as well as Pavese, and, with

Roger Shattuck, edited The Craft and Context of Translation (1961).

In addition, he has written penetrating commentary on Eliot's early

poetry and on Ruskin. He observes: "Translation, like politics,

is an art of the possible; if the translator has done his work the

best he can expect is that his reader, believing that the text has

been translated, not merely transcribed or transliterated, will feel

something of the contagion of the original."

("Eugenio

Montale" by Anthony Hecht.

Reprinted from the Summer 1998 Wilson Quarterly)